A People of Color's History of DSA, Part 4: DSA Looks Inward

Jul 6, 2020

July 07, 2020 03:44

By David Roddy and Alyssa De La Rosa

A People of Color’s History of DSA, Part 1

A People of Color’s History of DSA, Part 2

A People of Color’s History of DSA, Part 3

4: DSA Looks Inward

On Sunday, January 20, 1985, President Ronald Reagan was sworn in to a second term. DSA’s aspirations for a Mondale presidency–which DSA Labor Commission vice-chair Timothy Sears described as an opportunity to tell the truth about “[Reagan’s] phony ‘recovery’ with its staggering interest rates and declining standards of living, about the insane arms race, about the brutal budget cuts and the dirty little war in Central America–were now irrelevant.

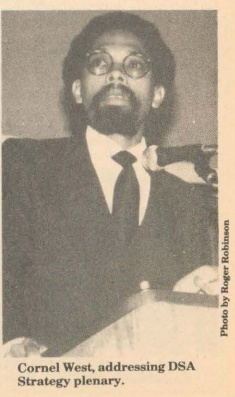

With the departure of Manning Marable from formal organizing within DSA in 1984, Cornel West took the mantle as the organization’s leading Black scholarly voice. West described DSA as, “The first multi-racial socialist organization close enough to my kind of politics that I could join.” Like other people of color that comprised DSA’s National Minorities Committee, West was critical of DSA’s decision not to back Jesse Jackson’s primary campaign, noting at the time, “Jesse Jackson’s bid for the Democratic nomination constituted the most important challenge to the American left since the emergence of the civil rights movement in the fifties and the feminist movement in the seventies. Unfortunately, the American left, for the most part, missed this grand opportunity.”

Following the defeat of Mondale, the Democratic Left devoted an entire issue to the question of building multi-racial coalitions, featuring leading Black members of DSA. In this issue, DSA leader and Jackson campaigner Gerald Hudson noted, “In the summer of 1983, few on the black left doubted either the necessity or the possibility of creating a multiracial coalition. We had always been convinced that black unity was necessary to achieve ‘liberation,’ but we no longer believed it to be enough. Racism could not be eradicated from American society, nor the abject poverty of a third or more of Afro-Americans eliminated, without the creation of a broad-based movement for social change. We had good reason to be hopeful. In Chicago, in Boston, around the candidacy of Jesse Jackson for the presidential nomination of the Democratic party, movements embodying these convictions had emerged onto the bleak landscape of American politics. By mid-1984, though few of us doubted the necessity of such a coalition, many of us had come to doubt its possibility.”

Hudson observed that “This subject has led to debates within DSA,” continuing that “Many black leftists were dismayed with and puzzled by the failure of important segments of the white left to support either Mel King’s mayoral campaign in Boston or Jesse Jackson’s presidential campaign. After all, the movements that grew around the candidacies of these men sought the empowerment of blacks through programs and demands that were of general benefit. Moreover, they made explicit overtures to the progressive white community. When that community did not respond, many of us were baffled and disappointed.”

Hudson locates “class first” politics as the source of the white progressive community reluctance to embrace the Rainbow Coalition, stating“ many democratic socialists came to believe that it was possible to discern a saving unity in a progressive economic program. The enormous appeal of this idea should not be underestimated. Did not the various oppressions out of which these movements arose have an economic aspect? Though racism or sexism was not reducible to their economic aspects, that they had such an aspect meant that their victims would benefit from an economically based progressive program.”

However, Hudson also observed, “Racism and sexism, insofar as they cannot be economically defined, go unopposed. When movements develop that do oppose these problems, they go unsupported by supporters of economically based coalition politics. Moreover, although white leftists may agree, for example, with the need for a full-scale effort against racism, in practice they often perceive the need for a coalition that includes constituencies that will not accept an anti-racist campaign (e.g., in Boston many leftists saw the need to mobilize racist white ethnics and called race a divisive issue in the 1983 mayoral race). Unfortunately, we have not been willing to step back and assess the failures of economically based coalitions and examine the complex issues involved in the building of such coalitions. ”

The Black Left and the Democratic Party

For West, the question of the rightward shift of the Democrats under Mondale, “the efforts for black unity and the political articulation of people of color in this country is now sophisticated enough to link its concerns with the downtrodden white working poor and the morally sensitive white middle class–as evidenced in the Jackson campaign. Soon the domestic front political pressure is brought to bear on the Democratic party to either embrace or exclude progressive forces. If it chooses the former, leftist possibilities loom large within the two-party system; if it chooses the latter, the only alternative becomes that of wholesale assault on the two-party system with the creation of a third political party.”

Still, some Jewish members of DSA remained skeptical of Jackson’s ability to attract Jewish voters. Paulette Pierce, at the time a member of the National Executive Committee of DSA’s Feminist Commission, wrote forcefully against this mindset: “Jewish progressives charge anti-Semitism, and black progressives suspect that a not too subtle racism may be at play. Without an open and perhaps heated exchange about this issue, the left will find it impossible to organize successfully within the black community, and black leftists already in progressive organizations like DSA will find it increasingly difficult to function… We are accused of engaging in racially polarizing politics and told to grow up and content ourselves with an integrationist strategy.” Pierce argued that “it is implicitly racist to assume that a coalition strategy which puts racial issues at the core of its politics cannot succeed. At best, such a position assumes that racism is presently so entrenched in our society that multi-racial alliances based on equality are currently impossible.”

Pierce also highlighted the chilling effect DSA’s endorsement of Mondale had on its small Black membership: “What is deeply troubling to many blacks including this writer is why so many of the constituencies targeted by the Rainbow Coalition stayed away and chose to support the neoliberal domestic and cold-war foreign policies of Walter Mondale…What is left unstated but may be the most important reason why white progressives stayed away is their fear that a coalition which puts antiracism at the center of its politics will alienate white labor, the constituency which many on the left still believe is essential to a successful progressive alliance…Obviously, Jackson was not the perfect candidate, but why must the black candidate be perfect? In anticipation of those who will ask, ‘Must we then accept the worst?’, Jesse was not the worst, Mondale was.”

Once again, those in the organization that were sympathetic to a sort of progressive Zionism took exception. Jeffry Mallow, who first criticized Marable for his endorsement of Jackson, responded to Pierce: “ The January-February issue of DEMOCRATIC LEFT was more than a little troubling for a Jewish socialist to read…we have Paulette Pierce’s apologia for Jesse Jackson’s antisemitism, wherein she…portrays the “hymie” remark as a one-time gaffe, rather than one of many antisemitic slurs which Jackson has uttered over the last decade” and “implies that Jews and other whites are racist because they refused to vote for a black anti-semite. Frankly, what attracts Jews to the democratic left is that they do not have to ignore their identity, divorce their people, and support everybody’s self-determination but their own. Let’s hope that, at least in DSA, it stays that way.”

The National Minority Commission and the 1985 Convention

The result of these divisions was the whitening of an already white-dominated organization. A report back from the 1985 convention noted that “Low participation of Black and Latino delegates, however, was a cause for concern. While every major convention plenary afforded minority representation from the podium, there were still fewer Blacks, Latinos, and Asian members at Berkeley than at the New York convention in 1983.”

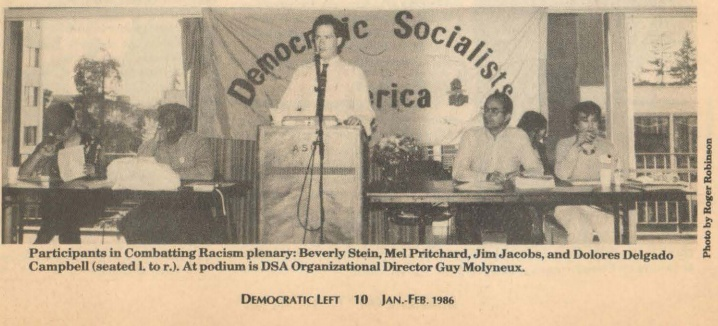

The Commissions, meanwhile, organized to change Harrington’s proposed economic policy draft for the 1985 convention arguing ”Any left should examine the economy from the point of view of the working class-this draft does not. Any accurate view of the US working class would have to notice that our society is stratified by race…It is the responsibility of a socialist organization to offer an analysis that includes within its perspective the economic realities of the entire people.” This language was accepted and the convention had a special plenary on race and the left where “Cornel West advocated an anti-racist, anti-imperialist strategy for the organization….Speaker Bev Stein described Portland’s role in building the Oregon Rainbow Coalition. Mel Pritchard of San Francisco spoke of the complex issues faced by DSA’s minority members. Jim Jacobs called for focused organizing to counter racism in white communities, and Dolores Delgado Campbell outlined Latino issues and concerns.”

Mel Pritchard, who came out of the New American Movement, was elected Organization Secretary for the National and Racial Minorities Committee at the 1985 Convention. He spoke to us about his frustration with DSA at that time, arguing that at the time of the merger DSOC “weren’t going to do any conscious anti-racism work. That was essential to their strategy in organizing…That’s not gonna work. I was hoping the merger might create more of a case to do anti-racism organizing.” However, he found the economism advocated by the former acolytes of Max Schactman previously in DSOC left little hope that the anti-racist work carried about in NAM by the likes of himself and Manning Marable could viably continue within DSA. Within a year he left “because the Shachtmanites who institutionally controlled DSOC controlled DSA”

Dolores Delgado Campbell, another speaker on that panel and co-chair of the Latino Commission at the time, related to us about the difficulties in retaining members of color in the organization: “We had people who were drawn by what we said we represented but it wasn’t enough for them. They were drawn by people like Manning Marable and Harrington recruited people like Dolores Huerto and Eleicaio Medina, who were major leaders in the UFW. ”

Nonetheless, Our Struggle/Nuestra Lucha–the Commissions newsletter–noted that “by majority votes the delegates supported our positions of the draft economic plans and Central American [solidarity] work,” indicating that the organization was broadly sympathetic to the work of the Commissions.

That year, the Latino and Anti Racism Commissions developed a series of local leadership “Facing Racism” talks, designed to highlight that “the authentic popular struggles of people of color are constituent parts of the left we seek to create.” Beverly Stein, the Co-Chair of Portland DSA, noted in Our Struggle/Nuestra Lucha that “the events were very successful, attracting new face to DSA and giving us an opportunity to educate, primarily the white left, about racism.”

Lookings Toward a future Rainbow Coalition

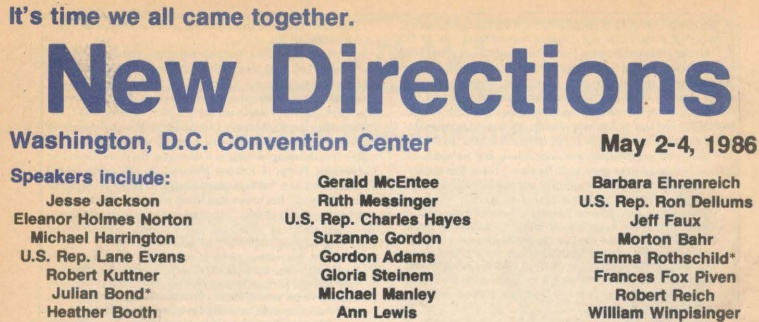

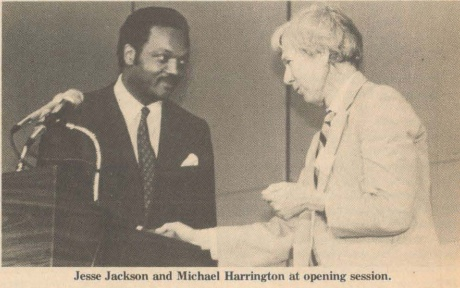

By the spring of 1986, DSA began warming relations with the Rainbow Coalition, with both Michael Harrington and Jesse Jackson addressing the opening session of a conference titled New Directions, which brought together the various strands of labor and social movements together to organize for a leftward shift within the Democratic Party.

Writing in the November/December 1986 edition of the Democratic Left, DSA Afro-American Commission chair Shakoor Aljuwani argued for DSA to take an active role in a potential Jackson 1988 campaign; “The Rainbow Coalition showed that it is possible to build a broad and powerful constituency of the “locked-outs and drop-outs,” the poor, and working people - groups that in other countries form the base of parties of the left. It was the major progressive voice to counter the onslaught of conservatism. It brought dynamism to the otherwise lifeless efforts of the Democratic party against the Reagan offensive.”

Aljuwani spoke to the need for the organization to embrace the consciously multi-racial strategy of the Rainbow Coalition, writing that “In the moral vision and political program of Jesse Jackson and the Rainbow Coalition there exists a deliberate attempt to embrace the interests and needs of Afro-Americans, the elderly, women, Hispanics, indigenous peoples, small farmers, Jews, Arabs, displaced industrial workers, trade unionists, gays, peace activists. The major problem has been convincing the three major liberal constituencies – labor, feminists, and Jews – of the seriousness of that vision and rhetoric. It is here that DSA can play a major and possibly even a key role. Some in DSA have raised the question of whether the Rainbow Coalition will be a tool only for ethnic political interests or become a broadly based multi-issue grassroots movement. Our response to the Rainbow can help shape the answer.”

Manning Marable, divorced from DSA following the 1984 Presidential election, noted the profound need for a progressive program to address rising rates of Black impoverishment: “In New York City, between 1980 and 1992, 87,000 private-sector jobs were lost. During the same time period, the number of African-Americans living below the poverty level increased from 520,000 to 664,000 people. The average black family in New York City now earns $24,000 annually, compared to over $40,000 a year for whites.”

Cornel West and the Development of DSA’s Anti-Racist Politics

In 1985, Cornel West–Chair of the Afro-American Commission preceding Aljuwani–developed a pamphlet for DSA’s strategic position on racism titled “Towards a Socialist Theory of Racism.” West laid out the following questions addressing DSA’s orientation to race: “What is the relationship between the struggle against racism and socialist theory and practice in the United States? Why should people of color active in antiracist movements take democratic socialism seriously? And how can American socialists today learn from inadequate attempts by socialists in the past to understand the complexity of racism?”

West criticized socialist movements that placed “racism under the general rubric of working-class exploitation…At the turn of the century, this position was put forward by many leading figures in the Socialist party, particularly Eugene Debs. Debs believed that white racism against peoples of color was solely a “divide-and-conquer strategy” of the ruling class and that any attention to its operations “apart from the general labor problem” would constitute racism in reverse.” West criticized this position as an “analysis that confines itself to oppression in the workplace overlooks racism’s operation in other spheres of life.”

He also criticized a conception of racism that “acknowledges the specific operation of racism within the workplace… but remains silent about these operations outside the workplace. This viewpoint holds that peoples of color are subjected both to general working-class exploitation and to a specific “super-exploitation” resulting from less access to jobs and lower wages. On the practical plane, this perspective accented a more intense struggle against racism than did Debs’ viewpoint, and yet it still limited this struggle to the workplace.”

West presented an alternative theory of racism for DSA, arguing the “racist practices result not only from general and specific working-class exploitation but also from xenophobic attitudes that are not strictly reducible to class exploitation. From this perspective, racist attitudes have a life and logic of their own, dependent upon psychological factors and cultural practices…To put it somewhat crudely, the capitalist mode of production constitutes just one of the significant structural constraints determining what forms racism takes in a particular historical period. Other key structural constraints include the state, bureaucratic modes of control, and the cultural practices of ordinary people. The specific forms that racism takes depend on choices people make within these structural constraints.”

West placed the “whitening” of DSA between its first and second National convention in the context of a historical “black suspicion of white-dominated political movements (no matter how progressive)” due to “the distance between these movements and the daily experiences of peoples of color…”

He elaborated that this disparity was amplified by “the disproportionate white middle-class composition of contemporary democratic socialist organizations creates cultural barriers to the participation by peoples of color,” and pointed out the paradox that “this very participation is a vital precondition for greater white sensitivity to antiracist struggle and to white acknowledgment of just how crucial antiracist struggle is to the U. S. socialist movement. Progressive organizations often find themselves going around in a vicious circle. Even when they have a great interest in antiracist struggle, they are unable to attract a critical mass of people of color because of their current predominately white racial and cultural composition. These organizations are then stereotyped as lily-white, and significant numbers of people of color refuse to join.”

West thought that “the only effective way the contemporary democratic socialist movement can break out of this circle (and it is possible because the bulk of democratic socialists are among the least racist of Americans) is to be sensitized to the critical importance of antiracist struggles. This “conscientization” cannot take place either by reinforcing agonized white consciences by means of guilt, nor by presenting another grand theoretical analysis with no practical implications.” He further argued that “a major focus on antiracist coalition work will not only lead democratic socialists to act upon their belief in genuine individuality and radical democracy for people around the world; it also will put socialists in daily contact with peoples of color in common struggle. Bonds of trust can be created only within concrete contexts of struggle. This interracial interaction guarantees neither love nor friendship. Yet it can yield more understanding and the realization of two overlapping goals: democratic socialism and antiracism.”

West’s piece became the primary anti-racist text of DSA, and whether followed or not, would serve as the road map to steer the organization forward.