A People of Color’s History of DSA, Part 2: DSA Enters the 80s

Sep 11, 2019

September 11, 2019 22:49

By David Roddy and Alyssa De La Rosa

(You can find part one in this series here.)

(All images from Democratic Left Online Archive)

The DSA was founded in March of 1982. Ronald Reagan had occupied the White House for a little over a year, but he had already fired 13,000 air traffic controllers who belonged to the Professional Air Traffic Controllers Organization (PATCO) union for going on strike, announced a federal payroll reduction of 63,000 employees by the end of 1983, cut taxes on the wealthy, and announced an arms buildup, declaring that the United States would produce the B-1 bomber and MX missiles. All the while the economy was sliding into recession.

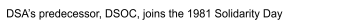

The introduction of austerity and recession hit Black workers the hardest. Manning Marable, at the time a leading figure in the founding of DSA, wrote, “Black workers suffered disproportionately from both unemployment and social-service reductions. In 1983, for example, 19.8 percent of all white men and 16.7 percent of all white women were unemployed at some point; for Blacks, the figures were 32.2 percent for men and 26.1 percent for women. Between 1980 and 1983, the median Black family income dropped 5.3 percent; an additional 1.3 million Blacks became poor, and nearly 36 percent of all African-Americans lived in poverty in 1983, the highest rate since 1966.” Writing in the Black Scholar, Marable defined Reaganism as “a political response by the most reactionary and racist sectors of monopoly capital to the present economic and social crisis” from which expelled “manifestations of random and institutional racist violence, vocal opposition to affirmative action, desegregation and civil rights laws.” For the United States, 1981 marked a year of economic and political reversals to the gains won by the civil rights and Black Power movements that defined the previous two decades.

However, Joe Schwartz, the former youth organizer for the Democratic Socialist Organizing Committee (DSOC), notes in his short history of DSA that while the United States government took a hard right, “Across the globe, a new ecumenical spirit of unity and optimism pervaded the Left, centering upon a rejection of statist and authoritarian conceptions of socialism. In Europe, the French Left gained the presidency for the first time. Numerous socialist parties adopted workers’ control as a programmatic focus and developed relations with Eurocommunist parties whose members concurred that democracy and civil liberties must be central to the socialist project. In the Third World, revolutionary movements in Nicaragua, El Salvador, Zimbabwe and elsewhere searched for a third way between inegalitarian capitalist development and authoritarian communist modernization.”

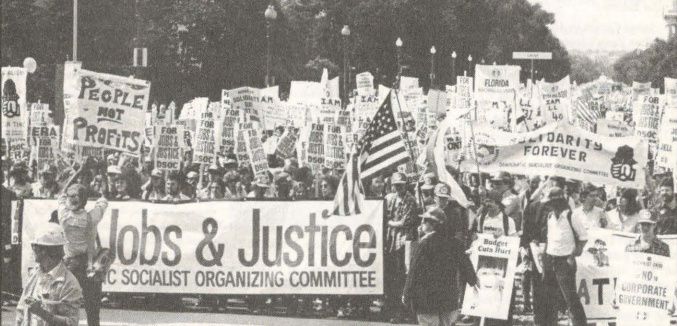

DSA, with its association with the Socialist International, saw continuity between its initial growth (reaching around 8,000 members in 1983) and this international trajectory. In addition, there was a ground swelling of social movements in the United States against Reaganism. In September of 1981, for instance, the AFL-CIO organized a “Solidarity Day” in support of PATCO workers that mobilized 260,000 people to march on Washington. In June of 1982, 1 million people gathered in New York’s Central Park against Reagan’s escalation of the Cold War and the threat of nuclear war. Also beginning in 1982, groups like Jesse Jackson’s PUSH and the NAACP began plans to mobilize a 20th anniversary March on Washington.

With preparations for an August 1983 20th anniversary march already underway during the period of DSA’s conception, the task of forming the fledgling DSA into an organization that could embrace the demands of national minority groups became vitally important. Manning Marable approached the organizational question of building a truly multi-racial organization that could take advantage of the moment by organizing a series of meetings and conferences in 1982 and 1983 to form a sense of organizational direction for members of color.

“This Will Not Be a Painless Process”

The first of such meetings occurred on October 2, 1982, in New York. Around 30 Black, Asian American and Latino East Coast DSA members met to discuss what DSA must do to build deep ties with various minority movements. The second meeting, occurring in January of 1983, occurred in San Francisco. Writing in the Democratic Left, John Spearman noted, “‘American Socialism and Minority Movements-Uneasy Alliance,’ was the title of the recent West Coast minorities conference, but it also serves to describe the state of affairs as DSA begins to focus on expanding beyond its white, middle-class base into minority communities.” Spearman added, that “Even though DSA is overwhelmingly white, it has a number of minority members in influential and highly visible positions in many important areas.”

Spearman argued, “[This] gives us a tremendous potential for organizing. Up to now, that potential has not been tapped. The most important reason for DSA’s failure in this area has been its lack of consciousness of the importance of the various movements of the oppressed in the fight for socialism. Given DSA’s historical and political roots and social composition, this is not surprising. Both predecessor organizations recognized the problem and need, but the New American Movement’s (NAM) anti-racist commission and DSOC’s Hispanic Commission, though positive efforts, were inadequate. The new committees will develop programs of action and recruitment as well as political positions on a wide variety of issues. In addition, they will work within DSA to strengthen understanding of minority movements.” Arguing that the economic downturn of the early 1980s and the increased racist sentiment of the white backlash personified in the election of Ronald Reagan would lead to a re-radicalization of national minority politics, Spearman contended that DSA should be poised to form alliances with minority groups to forge a multiracial socialist movement. Spearman ends his report “Given the histories, leadership and characters of the socialist and minority movements, this will not be a painless process, but it can be a constructive one.”

The San Francisco convention resulted in recommendations for the National Executive Committee to commit: to hiring a national staff person responsible for minority organizing, to create and fund the Afro-American, Latino, and Anti-Racism Commissions, $3000 to develop a theoretical journal, and the appointment of six people of color to the National Electoral Committee (NEC) to serve an advisory role before the October 1983 DSA National Convention. Additionally, members of color planned to put forward a resolution demanding a quota for nonwhite members to serve on the NEC.

In June of 1983, a third conference was held at Fisk University in Nashville Tennessee, where Marable was recently appointed as Director of the Race Relations Institute. Dolores Delgado-Campbell, once an organizer with the United Farm Workers and a member of DSOC’s Latino Commission, spoke to us about the need for an independent space for people of color that drove the discussions at the Fisk conference. “From my perspective having grown up as a Chicana in the Chicano movement and then a feminist, a lot of the shortcomings were that they thought they knew what should be done and that we should follow them. And I was like, bullshit. We have ideas of what we think needs to happen in the Chicano and Latino community as a whole and you’re not going to tell us what they are. But you should ask us and we can share that with you.”

Her husband, Duane Campbell, recalls; “It was a time of self-determination. So the African American Commission pursued an African American agenda, and the Latino commission pursued a Latino agenda, and the Anti-Racism Commission was created to help all the Anglos in the organization deal with racism. Because if you didn’t do that then the African Americans and Latinos were always left with the problem of ‘ok you guys go deal with anti-racism now’ which meant they couldn’t really do their own agenda. They had to spend their time dealing with racism in the organization rather than pursuing a Latino or African American agenda.”

Additional commissions, such as a Feminist Commission and a Religious Socialists Commissions, also solidified during the first year or so of DSA. However, the Latino, Afro-American, and Anti-Racism Commissions operated in conjunction with each other as the National and Racial Minorities Committee, releasing an internal news bulletin, Our Struggle/Nuestra Lucha, and, for a short period, a publicly facing journal titled Third World Socialists, which covered national liberation movements abroad and anti-racist work in the United States. Additionally, the DSA Feminist Commission’s journal, Women Organizing, devoted their Summer 1983 issue to Women of Color.

DSA Embraces Feminists of Color

In “Race, Reform and Rebellion,” Manning Marable notes that in the early 1980s there was a “decisive turning point in black feminist criticism.” In 1981, bell hooks produced her first major work, “Ain’t I a Woman,” which critically examined the history of sexism within Black communities. The same year, Angela Davis published “Women, Race, and Class,” which placed women in a central historical role in Black working-class liberation. 1983 saw the publication of “Home Girls: a Black Feminist Anthology,” edited by literary critic Barbara Smith, which brought together leading thinkers in the emerging Black feminist movement.

It was in this context that the Feminist Commission published Women of Color in the summer of 1983. In its introduction, a Feminist Commission member notes, “Special issues on women of color are a form of tokenism where they are not part of continuing multi-racial focus.” Frisch expressed hope that the development of Commissions and articles like those presented in “Women of Color” would, “Point the way for us to develop a multi-racial socialist-feminist analysis.” One prominent contributor was the poet Alice Walker, who had previously attended the conference at Fisk University. Additionally, writing from the perspective of a working-class Asian-Pacific, former DSA Youth Section organizer Angie Fa wrote that democratic socialism is relevant to the struggle of Asian-Pacific women as a community with “pressing needs of employment, discrimination, housing, bilingual education, needs which cannot be thoroughly met under capitalist society… Democratic socialism means structural changes which will allow Third World People to retain their own cultural identity, and to meet their full economic and social needs.” Lillie McLaughlin, Executive Secretary of the DSA National and Racial Minorities Coordinating Committee wrote about black women and the feminization of poverty. She noted DSA’s white majority and asked, “How can DSA expect to attract Third World Women when it has little or nothing to offer them in terms of their own experiences and, in fact, ignores them?” She argues, “It is up to DSA to decide what the organizational priorities will be…That change may threaten some of the entrenched ‘white power’ in the organization but it will mean that DSA will truly be the Democratic Socialists of America.”

Harold Washington

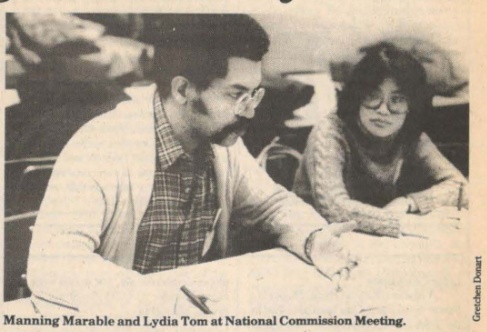

On February 3rd, 1983, insurgent candidate Harold Washington won the Democratic Primary in the Chicago mayoral race. Washington’s campaign represented a break with the usual Democratic Party machine politics of the city, and progressives around the country saw his victory as a blueprint for challenging Reaganism from the left. Manning Marable argued that the campaign differed from the Black electoral efforts that preceded it because it challenged “not only the exploitation of Black workers, but the social manifestations of the racial division of labor from housing, inadequate education, and so forth.” While being outspent 10 to 1 by incumbent Mayor Jane Byrne, organizers around the Washington campaign enrolled over 180,000 new Black voters.

Chicago DSA threw its resources into the Washington campaign. Writing in the April 1983 Democratic Left, Chicago DSA member John Cameron reported:

“The historic significance of the Washington bid led Chicago DSAers to make an early and total commitment to his campaign. Washington appeared at the regular meeting of the local last December, receiving unanimous enthusiasm from the 165 members present. An initial fundraising appeal generated nearly $1,000 in donations. Local members set up a phone bank to contact everyone in the local to request their active participation in precinct, fundraising, and election day work. By mid-January, over 80 DSAers were involved as precinct canvassers, areas coordinators or staff. By the end of the primary campaign, DSA members had contributed $3,000 for Washington. Several DSA members played key roles in the campaign organization. Milt Cohen coordinated voter registration activities and served as liaison with many area progressive groups. Roberta Lynch was precinct coordinator for the Northside/Lakefront Area of the campaign where many DSAers were active. Other DSA members helped win support for Washington in their unions and community groups. Although by no means alone, DSAers were among the few progressive groupings based outside the Black community to fully support the Washington effort.”

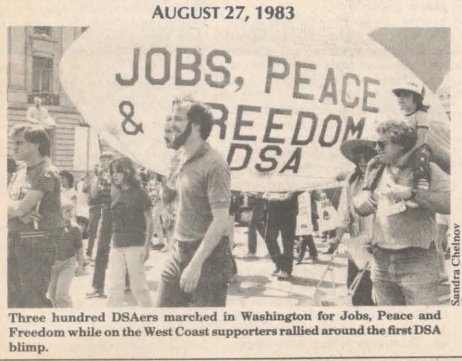

March on Washington

Beginning in 1982, civil rights organizations, trade unions, churches and leading Black politicians began to plan for the 20th anniversary of the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, where 250,000 people marched on Washington for civil rights and Martin Luther King Jr. gave his now-famous ‘I Have a Dream Speech.” The organizers of the 1983 march added “Peace” to the demands of “Jobs and Freedom.” In 1982, 20% of working-age Black men were unemployed, a 300% increase since 1960. This was in part tied to Reagan’s austerity budget: Federal agencies dismissed minorities at a rate 50% higher than whites in 1981, and the rate of lay-offs doubled in 1982. Increased military expenditures did not offset these losses, as arms production tended to be less labor-intensive than other kinds of government spending. Members of the Congressional Black Caucus (CBC) introduced an “Alternative Budget” in 1982 to attempt to shift funds from military to peacetime projects, and CBC and DSA member Congressman Ron Dellums introduced an alternative Appropriations Bill aimed at reducing military funding. Both died in the Democrat-controlled House. The additional demand of “Peace” therefore tied the economic plight of African Americans in the early 1980s directly to Reagan’s military expansion.

Manning Marable wrote in the February 1983 Democratic Left: “The message is clear: more than any other sector of the American public, Blacks have a clear stake in the campaign to end the nuclear arms race and to reduce conventional weapons. We may oppose the MX missile on moral grounds, but more than this, we must wage an unrelenting campaign within Black schools, churches, and labor halls to create a popular movement relating defense spending to jobs.”

DSA organized a visible contingent at the march. The DSA Youth Section went so far as to move its annual conference to Washington D.C. to maximize member participation. In San Francisco, DSA participated in a sister rally. While the presence of an organized left at these rallies was notable, it was a speech by Jesse Jackson that set the progressive agenda for the 1980s:

“We must move as a nation from racial battleground to economic common ground… In 1980 Reagan won with a reverse coalition of the rich and the unregistered… Black Americans, Hispanics, women, change your mind… Our day has come… From the slave ship to the championship, march on! From the out-house to the state-house to the court-house to the White House, we will march on.”

The crowd responded with thousands rising to their feet to chant “Run, Jesse, Run.” The question of building a multiracial coalition with the power to topple Reaganism coalesced around Jesse Jackson, making his 1984 Presidential run almost certain.

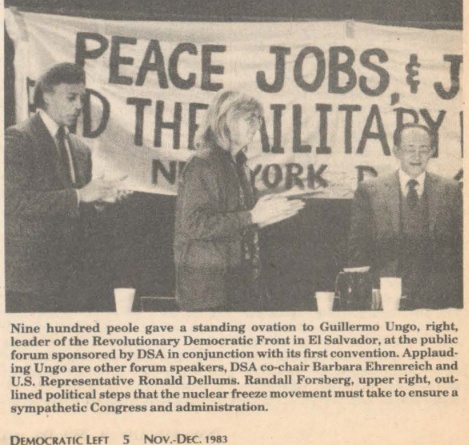

DSA’s First National Convention

On the weekend of October 14, 1983, DSA held its first National Convention. About 300 delegates from 60 cities convened in New York. The National and Racial Minorities Committee launched by Marable had a notable presence, and the Committee demand for minority representation was met, though, Latino Commission member Dolores Delgado-Campbell notes, not without controversy. “In ‘83 our big struggle was to get a quota on the NPC. We wanted three men of color and three women of color on there. That was a big battle but we won. [DSA Founder Michael] Harrington was on our side too.”

Leftist journalist John Judis of In These Times stated that the convention seemed split between what he termed “Greens,” or those wedded to the new social movements such as feminism or the peace movement, and “Reds,” who were committed to working within the labor movement. Responding to Judis in the Democratic Left, Chair of the recently established Afro-American Commission Cornel West argued: “ I would suggest that a new emancipatory perspective is in the making-and fermenting in the bowels of DSA. Such a perspective preserves the powerful critique of class exploitation (including its imperialist expressions) and the normative call for workers’ self-management of economistic Marxism; incorporates the concerns for sexual freedom, racial, gender and sexual orientation equality and ecological balance of cultural leftism; accentuates the precious ideals of substantive democracy and liberty of democratic radicalism; and learns from the sobering tough-minded every-day engagement of pragmatic progressivism” but “ only serious and sustained exchange can take us beyond the obfuscating categories of “red vs. green” and move us toward illuminating conceptions of the debate we so desperately need.”

How DSA would develop this emancipatory perspective became vital in the week after the convention. The Reagan Administration launched “Operation Urgent Fury,” landing US troops in Grenada in an effort to topple the People’s Revolutionary Government. The “Peace” demand of the 20th Anniversary Washington Marchers became vitally important.

The first few years of DSA and the first term of Ronald Reagan was a time of both immense hope and fear. The victory of Harold Washington and the momentum around the 20th Anniversary March on Washington suggested that a newly mobilized Black electorate could counteract the racist backlash of Reaganism. With its commission system, DSA struggled to grow away from its white, middle-class origins by promoting programs to give room for people of color to self-organize. It embraced movements for self-determination in the Third World, rejected Reagan’s militarism, and supported new feminist thinkers concerned with the struggles of women of color.

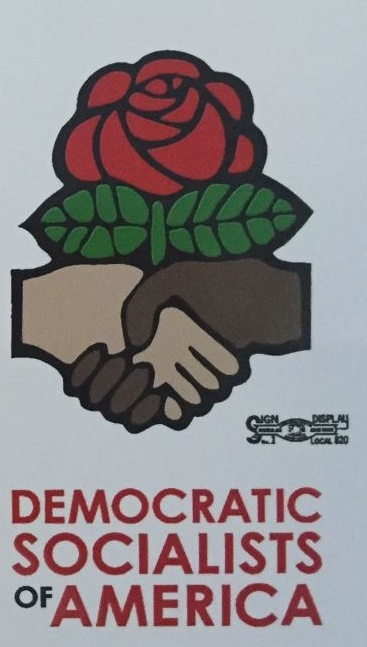

John Spearman’s observation that making a truly multiracial DSA would “not be a painless process” proved prophetic as Jesse Jackson officially announced his candidacy for President in November of 1983. A month before, the DSA National Convention voted to change the organization’s logo from a single fist holding a rose to a rose emerging out of a black hand and a white hand that are shaking. Whether DSA could meet the ideal embodied in this image, in the words of Lillie McLaughlin if “DSA will truly be the Democratic Socialists of America,” was still an open question.