A People of Color's History of DSA, Part 3: DSA and The First Rainbow Coalition

Dec 4, 2019

December 04, 2019 23:45

By David Roddy and Alyssa De La Rosa

A People of Color’s History of DSA, Part 1

A People of Color’s History of DSA, Part 2

3: DSA and The First Rainbow Coalition

In the summer of 1984, the National Executive Committee of the Democratic Socialists of America polled its members ahead of the Democratic National Convention and decided to endorse former Carter Vice President Walter Mondale as the organization’s choice for the Presidency over the Black insurgency within the Democratic party led by Jesse Jackson. In many respects, it was a counterintuitive decision on the part of the organization: Jackson’s initial political sponsors included Congresspersons Ron Dellums and John Conyers, the most left members of the Black Congressional Caucus and prominent members of DSA. The successful Harold Washington mayoral campaign in Chicago and the narrow defeat of Black socialist Mel King in Boston in 1983 demonstrated what left-wing critic of DSA Mike Davis described as the practicality of a “Rainbow Coalition’ of minority communities, white progressives, and elements of the trade-union movement.”

The AFL-CIO officialdom, led by Lane Kirkland, however, had already coronated Walter Mondale as the Democratic Party’s, and organized labor’s, best chance against a two-term Ronald Reagan presidency. The powerful New York chapter of DSA, held by DSOC stalwarts Michael Harrington, Irving Howe and Bogdan Denitch, closely followed the labor officialdom’s line. All three were strongly influenced by the work of the American Trotskyist Max Shactman, who viewed the AFL-CIO as the only true representative of the American working class. Harrington and those close to him in DSOC broke with the followers of Schactman to incorporate New Politics–the social movements of the 60s and 70s–into a leftwardly realigned Democratic Party. The endorsement of Mondale by the National Organization for Women in December of 1983 seemed to indicate that such a realignment could amass a social bloc large enough to unseat Reagan.

This position, however, was not shared by all members of DSA. In particular, the newly created Hispanic and Afro-American Commissions, part of a broader National and Racial Minorities Coordinating Committee led by Manning Marable, strongly supported Jackson. In the January 1984 issue of the Democratic Left, Marable argued, “How can we seriously expand the electorate in 1984 to include millions of young people, national minorities, women and poor people? …Given our meager resources, socialists should be involved in campaigns that build coalitions with liberal and left constituencies within national minority communities. And that raise political issues from a democratic left perspective…. At a national level, the Jackson campaign is the Harold Washington/Mel King coalition, bringing together representatives of every element of the democratic left.”

DSA was forced to choose between the mainstream liberal and Labor backed Mondale and the insurgent candidacy of Jackson. Marable’s observation that Jesse Jackson represented a left-wing alternative to Mondale was rooted in the increasingly anti-corporate and anti-imperialist rhetoric of the campaign. Jesse Jackson had not always held such views so clearly. Just one year prior, at a conference for the New Orleans Business League, he promoted some form of Black capitalism as a means to ameliorate urban poverty, stating confidently that “the marketplace is the arena of our development” (Marable pg. 264). Influenced by the successful progressive campaign of Harold Washington, as well as the influence of progressive Black clergy members and veterans of the New Left filling in the support staff for his Presidential run, Jackson became an unambiguous left alternative to Mondale that, while not gathering the backing of mainstream Civil Rights and Labor organizations, spoke directly to the needs of national minorities suffering under Reaganism with a social-democratic program of peace, jobs, and wealth redistribution.

“Hymietown” and Fall Out

In February of 1984, Washington Post reporter Milton Coleman overheard Jackson refer to Jews as “Hymies” and New York City as a “Hymietown.” Hymie is an uncommon slur for Jew, and at first Jackson denied using the term, then admitted to it, and finally apologized, stating that “It was not in a spirit of meanness, an off-color remark having no bearing on religion or politics…. However innocent and unintended, it was wrong.” Before his apology, however, Eddie Murphy mocked his gaffe on Saturday Night Live, making Jackson’s comment a household subject of discussion.

Duane Campbell, then head of the Anti-Racism Commission, recalls that this incident played a stronger role in DSA’s ultimate endorsement than the ideological orientation of DSA’s leadership. “In 84 the commissions supported Jesse Jackson. In that era, the New York City local dominated things and Jesse had the Hymie Town comment, so they went bonkers about Jesse. But they wouldn’t have endorsed him anyway. They went with Mondale. We endorsed Jesse.”

In the May/June 1984 issue of the Democratic Left, DSA member Jeffy Mallow commented on a piece by Marable advocating for a Jackson endorsement, writing that “I hope the article went to press before the “Hymietown” incident. Otherwise, what we have here is another example of the Left’s sordid history of supporting alliances with anti-Semites because all the “progressive” people are doing it.” Marable responded that “No one recognizes Jackson’s errors and contradictions more than the progressives who work within the Jackson coalition. Yet support for Jackson is absolutely essential to move the Democratic party to the left-and if Jackson was not running, Mondale would surely lose to Reagan, because of the lack of electoral involvement from minorities. ‘Anti-Jewish racism’ is no less of a ‘sin’ than anti-Black racism, or sexism, or homophobia. But your position, which I respect, does not square with the unfortunate realities of racist and sexist America-which we are attempting to change, one step at a time…I wrote the original piece in November/December 1983, and revised it slightly in January. So there’s no way I could have predicted the atrocious “Hymie” incident. I would disagree, however, in your characterization that Jackson is a “‘‘racist candidate’ and ‘progressive Jew-hater.’ Jackson’s comments must be repudiated, but without a rejection of the overall progressive content of his campaign.”

“Hymie,” short for the Jewish name “Hyman,” is a seldom-used perjorotive term. Most sources, in fact, trace its origins to the Jackson comment and consequent Murphy sketch. In Jackson’s apology, he stated that he was “shocked” that “something so small has become so large that it threatens the fabric of relations that have been long in the making and must be protected.” It seems unlikely that Jackson would be shocked by this. In fact, a group calling itself “Jews Against Jackson” formed in November 1983 as he began his campaign. The roots of the animosity of many Jewish members of DSA towards Jackson did not begin with the utterance of the word, but instead with a growing distrust between the Black and Jewish left, particularly in New York, since the mid-1960s.

A Fractured Alliance

In his 1985 book, Black American Politics, Marable wrote that “for over two decades, many Black activists had been increasingly critical of Jewish involvement with Black political affairs.”

In 1967, Black Power advocate Floyd McKissick was appointed the director of the Congress on Racial Equality (CORE). Previously, CORE had been a pivot point between the largely white and often Jewish campus New Left, organizing the 1964 “Freedom Summer” aimed at mass black voter registration in Mississippi. This effort led to a highly publicized lynching of two young Jewish men from New York, Andrew Goodman and Michael Schwerner, along with Black Mississipi activist James Chaney. Through this episode, CORE received generous funding from Jewish organizations. CORE’s embrace of Black Power rhetoric, however, saw the end of most of these funds. The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), another powerhouse of the Civil Rights movement, received a strong rebuke from the Jewish American Congress for publishing a brief article in support of Palestine during the Six-Day War. The article was condemned as “shocking and vicious antisemitism.” This incident, as well as the rise of Black nationalist Stokeley Carmichael within SNCC’s leadership, led the organization towards bankruptcy.

In his 2019 book “Black Power and Palestine,” historian Michael Fischbach notes that in the context of the late 1960s, “one’s stance on the Arab-Israeli conflict rose to such importance within the two wings of the black freedom struggle. It was not merely because blacks held different perspectives on that issue but also because it became a crucial reference point by which they created and articulated their respective visions of identity, place and struggle in America.” As the 1960’s progressed, elements of the Black Power movement increasingly saw their movement as part of a broader global struggle for Third World liberation. This skepticism towards Israel intensified after the 1973 Yom-Kippur War led to increased diplomatic ties between Israel and Apartheid South Africa. The Palestinian Liberation Organization, in turn, drew parallels between their struggle with Israel and liberation struggles in Africa and the United States.

Concurrently, Jewish politics in the United States took a relatively conservative turn. Arnold Lindhart of New York’s American Jewish Congress observed in 1984 that American Jews had become more aligned towards candidates and policies that “favor issues such as neighborhood preservation–an issue non-whites often view with distrust and perceive as meaning segregation–rather than the old liberal concerns such as social welfare.” Manning Marable noted in Black American Politics that “many Jewish groups actively opposed racial quotas in affirmative action programmes, while blacks demanded quotas as an effective means of redressing discrimination.”

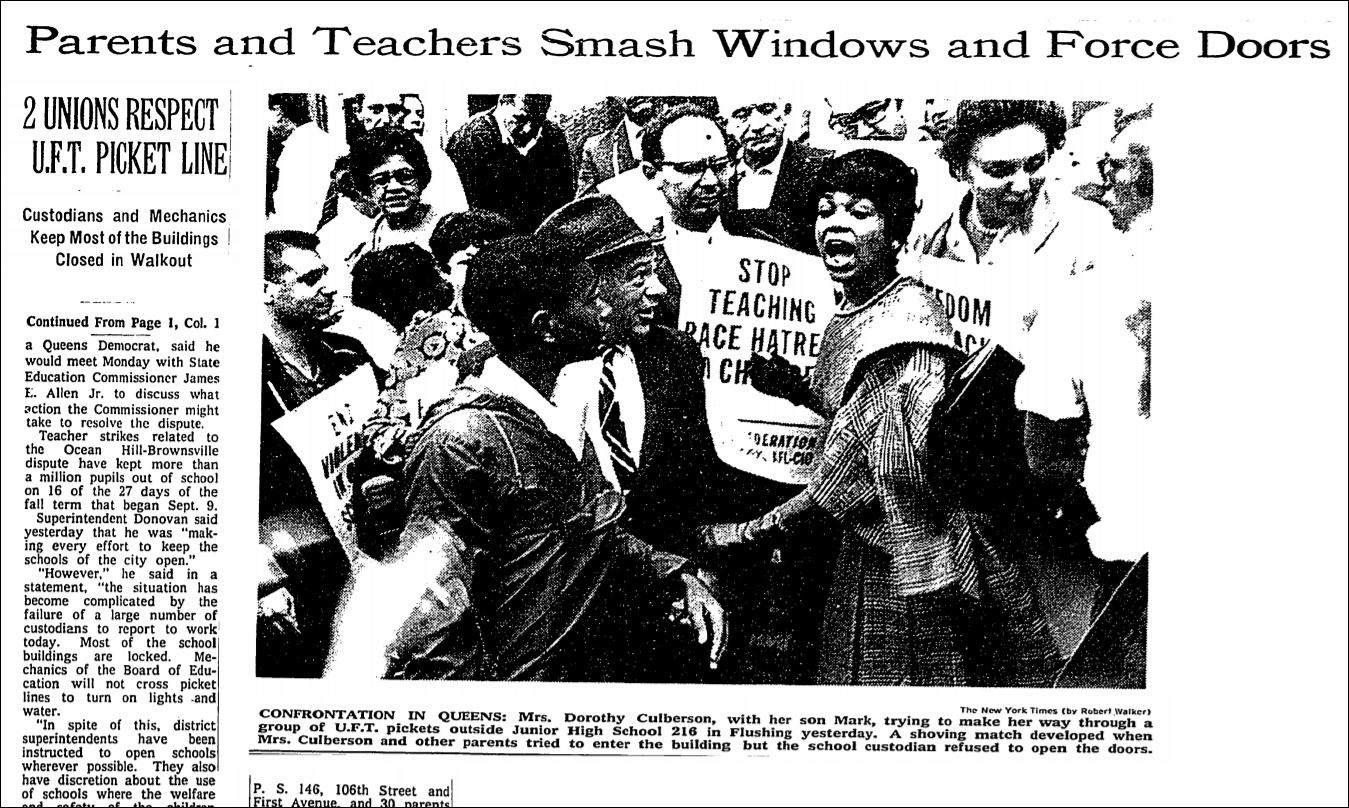

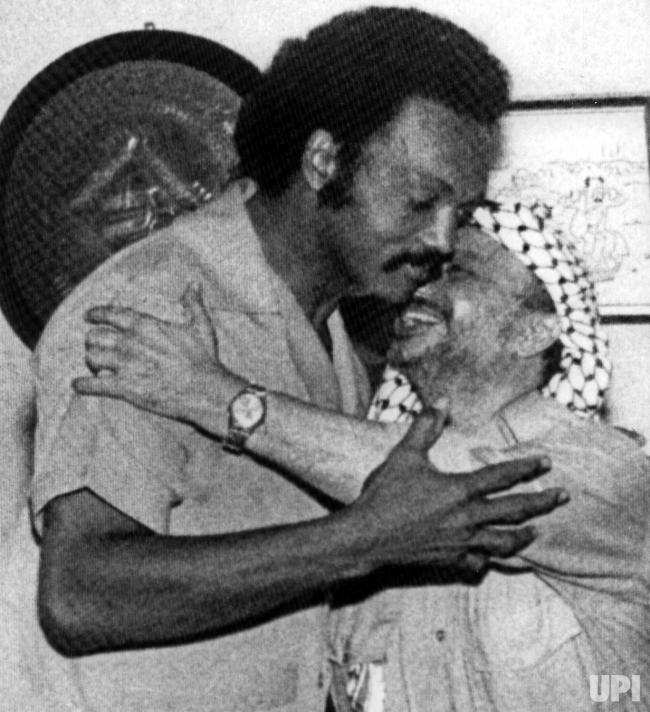

This tension was particularly strong in New York, where in 1968 teachers staged a massive strike in response to the Ocean Hill-Brownsville School District reassigning white teachers to different schools during an experiment with community school control. The strike pitted the United Federation of Teachers, led social democrat Albert Shanker, against large segments of the Black community, including teachers organized under the African-American Teachers Association. The district had historically been primarily Jewish, and the experiment in community school management brought the majority white and Jewish UFT teachers in direct conflict with a growing Black Power movement. For instance, armed Black Panthers protected strike-breakers at picket lines and rallies organized by Shanker were met with chants of “You’re a racist, Shanker!” Shanker, in turn, portrayed the opposition to UFT as being driven by anti-Semitism. UFT produced picket signs proclaiming “CIVIL RIGHTS FOR TEACHERS” and “STOP TEACHING RACE HATRED” targeted at the perceived and sometimes obvious anti-Semitism of some members of the Black community. Sheila D. Collins, a field organizer for the Jackson campaign, observed that “just as blacks have absorbed the Jewish stereotypes available in the general culture, so American Jews participate in the racism of white society. Because the groups’ particular histories of genocide and prediction, both are unusually sensitive to any indications of threats to the group and thus any threat–real or perceived–is likely to carry a high emotional charge.”

Jesse Jackson was not silent on this rift within the labor movement. In a highly critical 19 86 book on Jackson phenomenon, authors Bob Faw and Nancy Skelton note that “Jews winced when Jackson wrote: ‘There are tensions in the labor movement, where blacks constitute a large percentage of the workers at the bottom but Jews dominate the leadership at the top…. Tensions between black renters and Jewish landlords are just a few recent historical events that have brought to a head the present state of affairs…. When there wasn’t much decency in society, many Jews were willing to share decency. The conflict began when we started our quest for power. Jews were willing to share decency, not power.”

It was in this charged atmosphere that Bayard Rustin, a leader in the early Civil Rights movement and long-time member of the Socialist Party of America, published an ad in the New York Times and the Washington Post on June 28, 1970, titled “An Appeal by Black Americans for the United States Support to Israel.” Fischbach notes that Rustin “had reason to worry…about Jews abandoning ongoing political work with blacks.” Rustin’s support for Israel was premised on the need for Jewish support in the continuing struggle for Civil Rights. The advertisement controversially argued that “we…support Israel’s right to exist for the same reasons that we have struggled for freedom and equality in America” and that “For the present this means providing Israel for the full number of [fighter] jet aircraft it has requested.” Rustin’s letter was applauded by some center-left Jewish, labor, and Civil Rights organizations and derided by Black Power and Third World Liberation activists.

The Andrew Young Affair

This schism would deepen in 1970 with the creation of the Black September Organization in Palestine, a clandestine terrorist group linked to the PLO. Black September took its name from battles between the PLO and Jordan that September. In the United States, the Black Panther Party announced that “The struggle of the Palestinian people for their freedom and liberation from US imperialism and its lackeys is also our struggle.” This echoes a statement made a year earlier by PLO leader Yasir Arafat that the “Palestinian Liberation Movement considers itself part of the people’s struggle against international imperialism…The mask may differ, but the face remains the same.” The Black September Organization sought to carry out a series of terror attacks against states backing Israel, most notably the 1972 Munich Massacre, in which Black September militants held hostage and executed eleven Israeli athletes with the help of West German Neo-Nazis at that year’s Summer Olympics. The resulting public outcry led to the dissolution of the Black September Organization. In 1974, Rustin wrote an opinion piece entitled “The PLO: Freedom Fighters or Terrorists?” against the UN General Assembly inviting the participation of the PLO within their deliberations.

In October of the following year, Egypt and Syria launched joint attacks on Israel. The United States was quick to provide aid to Israel, while the Soviet Union backed Syria and Egypt. Then in 1975, PLO militants, at the time using southern Lebanon as a staging area for missile strikes against Israel, entered into conflict with right-wing Christian militias, beginning the Lebanese Civil War. The Arab-Israeli wars served not just as a line of demarcation between accommodationists and revolutionary elements in the Black freedom struggle but also between those loyal to the Soviet Union versus the United States.

In 1977, President Jimmy Carter appointed Civil Rights icon Andrew Young to be U.S. ambassador to the United Nations. In July of 1979, Young attempted to delay a United Nations call for the creation of the Palestinian State, meeting with the UN representatives of several Arab states in the process. As a term of their agreement, they insisted that the PLO representative must also agree to the delay. Young met with the representative of the PLO to the UN on July 20th, breaking an agreement between the United States and Israel that the U.S. would not meet with representatives of the PLO. Isreali intelligence leaked an illegally acquired transcript to the press, prompting President Carter to dismiss Young, the first Black Ambassador to the United Nations, from his post. It was later revealed that that the Jewish American Ambassador to Austria, Milton Wolf, had met with the PLO three times before Young, prompting widespread anger across the spectrum of Black political leadership. The New York Times notes “In a series of interviews in the last two weeks, Jews said they feared that statements by blacks critical of Jews might set off a wave of anti‐Semitism and make it harder for the United States to continue its support of Israel; black organizations said they had been threatened with the loss of contributions by some Jews who in the past have given heavily to civil rights causes.” Jesse Jackson said the Black-Jewish relations were “more tense than they’ve been in 25 years.”

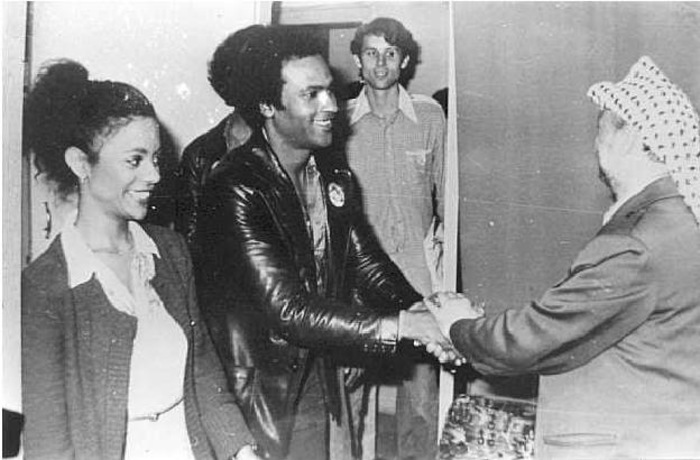

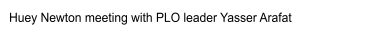

In response to the Young affair, in 1979 Jackson–through his organization Operation PUSH (People United to Save Humanity)– met with Arafat in an effort to in an effort to “establish a beachhead for our government to see whether there is a possibility for it to assume its responsibility, which is, in fact, to open up talks (with the PLO) and reconcile America’s several interests in the Middle East.” Images of him embracing the PLO leader became the center of some media controversy, viewed by some as evidence of his ambivalence towards mending the frayed ties between Black and Jewish Americans.

In 1983, these diplomatic relationships translated to Jackson’s campaign receiving strong support from the growing Arab-American community, with thousands donating to his campaign.

Marable notes that in New York, “the decline of the local white population and the rise of black political activism has made the Jewish community even more apprehensive and concerned with protecting its political ‘power.’ Consequently, many New York blacks concluded that Jewish criticism of Jackson was actually an attempt to maintain local white ethnic hegemony over the national minority electorate.”

The 1984 DNC

In the July/August issue of the Democratic Left, Harold Meyerson claimed that “on the level of presidential politics, the Democrats have become primarily a party of social movements.” This was certainly true. The relative conservatism of Walter Mondale was still backed by the forces of organized labor, civil rights, women’s rights, and environmentalists. However, Meyerson also argued that “it is an incomplete transformation. Labor and feminists got their candidates but they had to leave much of their program behind. Paradoxically, the platform passed by the convention of the movements was the first in decades to contain no reference to full employment or national health insurance.” Meyerson continued that “black organizations were among the few that stood with labor at the outset of the Reagan years in defense of the public sector. And while Jackson himself seemed periodically ill-suited for the task of coalition-building, convention support for much of his program extended well into both the labor movement and the women’s movement. Indeed. the Women’s Caucus endorsed several of his planks, which when brought to the floor received two-and-one-half times the number of votes that he himself was to receive the following night.”

Jackson’s 84 speech critiqued Reagan’s presidency on moral grounds “Its policies and programs have been cruel and unfair to working people. They must be held accountable in November for increasing infant mortality among the poor… If we cut that military budget without cutting our defense, and use that money to rebuild bridges and put steelworkers back to work, and use that money and provide jobs for our cities, and use that money to build schools and pay teachers and educate our children and build hospitals and train doctors and train nurses, the whole nation will come running to us.”

In an effort to appeal to minority and women voters, Mondale chose Geraldine Ferrero to be his running mate, the first woman selected for Vice President by a major capitalist political party in United States history. Herald Meyerson noted that the combination of Jackson’s speech and Ferrero’s nomination “distinguished the proceedings” and became “the common property of the entire convention, and the party found it could enthusiastically be guided by and in turn encompass the black and women’s movements.”

Nonetheless, Mondale refused to hire Rainbow supporters into campaign positions, and Jackson refused to endorse Mondale until he could “inspire the masses.” Instead, Mondale appealed to a growing white professional class by calling for an additional increase of the military budget, a twenty-nine billion reduction in social and civilian expenditures, and supported Reagan’s imperial incursion into Grenada. As Mondale’s campaign solidified its political platform, it became clear that DSA, despite its rhetoric, had failed to move the Democratic Party leftward by not backing the only candidate that ran on a clear progressive platform.

This failure was noted by some DSA members following the National Executive Committee’s endorsement of Mondale. In the September-October 1984 edition of the Democratic Left, members of the Steering Committee of East Bay DSA wrote, “An explicit acknowledgment of the tremendous contribution made by Jesse Jackson and the Rainbow Coalition in articulating a left program and mobilizing a large constituency behind that program during the primaries and at the convention.”

The controversy within DSA surrounding the Jackson campaign laid bare deeply rooted contradictions within the nascent organization. In “Prisoners of the American Dream,” Mike Davis argued that “with its explicit anti-imperialism, the Jackson campaign probably invited an impossible leap from DSA leaders like Harrington or Howe who have given life-long dedication to liberal zionist and anti-Communist causes. Moreover, the absence of any serious debate about the election in DSA, except from a passionate group of Black members leaves open…the question of whether even…the grassroots of that organization are capable of challenging its traditional mortgage to Israel and the Cold War, or of realigning the organization toward mass political currents that do not have the endorsement of liberalism.”

The passionate group of Black members, unfortunately, were increasingly alienated from DSA. DSA Vice-Chair Manning Marable, the sole Black socialist voice syndicated across American Black newspapers, no longer appeared in the pages of the Democratic Left. In a 2014 interview with Z Magazine, he recalled:

“I had a number of friendships in DSA. I respected Michael Harrington, who was the driving force in the organization, but I strongly disagreed with his strategic view of how to achieve socialism in the United States. Michael believed that the Left should be “the Left of the possible” inside the Democratic Party and that it should have a close working relationship with liberalism to keep liberalism honest. I felt that we needed an inside-outside approach. I believed that our emphasis should be balanced between supporting progressives in the Democratic Party and trying to initiate independent political motions—and doing activism in the non-electoral arena. That perspective never won out. So by 1985, I was basically moving away from the organization—not an antagonistic break—just a recognition that DSA’s model probably would not be successful in this country in constructing a viable Left alternative capable of achieving state power.”

Marable’s exit from the organization was a tremendous loss for both the organization’s internal intellectual dialogue and for its capacity for Black leadership. Writing in “Black American Politics,” Marable noted that “The intense socio-economic crisis of the 1980s in black America created the social foundations for a black revolt against the Democratic Party, but given the lack of a socialist alternative, the revolt occurred within the Democratic Party.” After the debates over Jackson, it is clear that, for Marable and many other Black members, those social foundations would not find root in the Democratic Socialists of America.